I’m so excited. On last Wednesday Flexiant has announced the acquisition of the Tapp technology platform and business. I met the guys behind it quite a while ago and I have never refrained from remarking how great their technology is (see here). I recognized a trend in their way of addressing the cloud management problem and I’m so glad to be part of, right now.

Disclaimer. I am currently working for Flexiant as Vice President Products. I have endorsed this acquisition and I am fully behind the reasons and convinced of the potential of it. This is my personal blog and whatever you read here has not been agreed with my employer in advance and therefore it represents my very personal opinion.

Right after the acquisition (read more about it here) we’ve heard tremendous noise on social networks and the press. David Meyer (@superglaze) of GigaOm in particular wrote up a few interesting comments and he picked up well the reasoning behind it, but he also ended the article with an open question:

“This [the Tapp technology platform] would help such players [Service Providers] appeal to certain developers that are currently just heading straight for EC2 or Google.

Of course, this is ultimately the challenge for the likes of Flexiant – can anything stop those developers going straight to the source? That question remains unanswered.”

Well, I’d like to answer that question and say why I’m actually convinced there is a lot of value to add for multi-cloud managers.

Much has been written these days from the business side of the acquisition and I don’t have anything meaningful to add. Instead, I would like to raise a few interesting points from a technology point of view (that’s my job, after all) and unveil those values that are maybe not so obvious at the first sight.

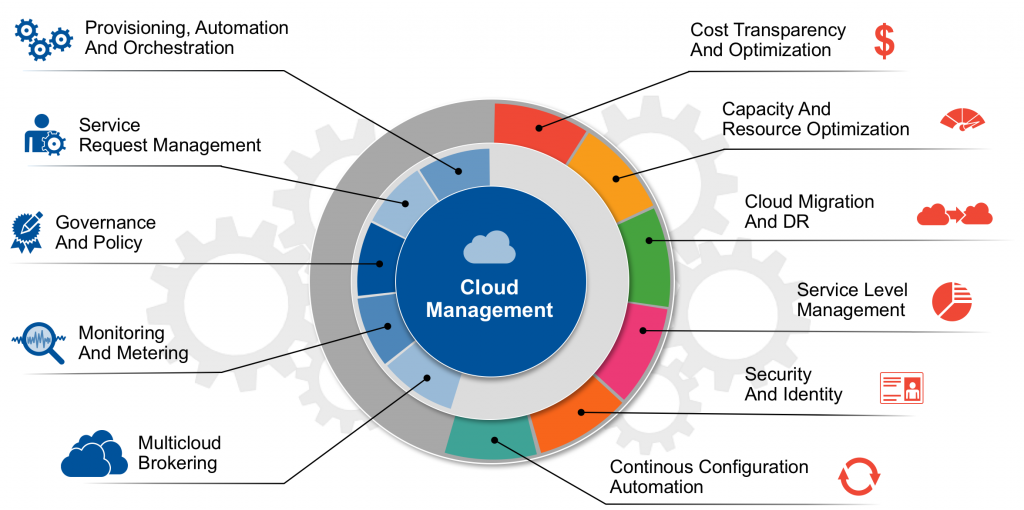

Multi-cloud management

Multi-cloud management per se has a very large meaning spectrum. There are multi-cloud managers brokerage, therefore primarily on getting you the best deal out there. Despite this is a good example about how to provide a “multi-cloud” value, I’m still wondering how they can actually find a way to compare apples with oranges. In fact, cloud infrastructure service offerings are so different and heterogeneous that being simply a cloud broker will make it extremely difficult to succeed, deliver real value and differentiate. So, point number one: Tapp isn’t a cloud brokerage technology platform.

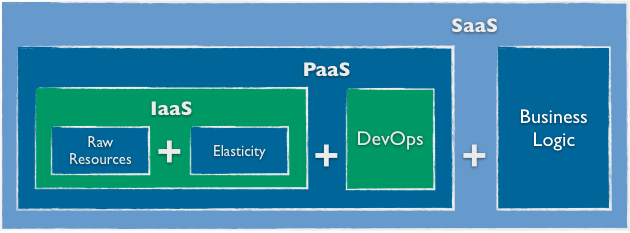

Other multi-cloud managers deliver value by adding a management layer on top of existing cloud infrastructures. This management layer may be focused on specific verticals like scaling Internet applications (e.g. Rightscale) or providing enterprise governance (e.g. Enstratius, now Dell Multicloud Manager). By choosing a vertical, they can address specific requirements, cut off the unnecessary stuff from the general purpose cloud provider and enhance the user experience of very specific use cases. That’s indeed a fair point but not yet what Tapp is all about.

So why, when using Tapp, developers won’t “go straight to the source”? Well, first of all, let’s make clear that developers are already at the source. In fact, to use any multi-cloud manager you need an AWS account or a Rackspace account (or any other supported provider account). You need to configure your API keys in order to enable to communication with the cloud provider of choice. So if someone is using your multi-cloud manager, it means that he prefers it over the management layer provided by the “the source”.

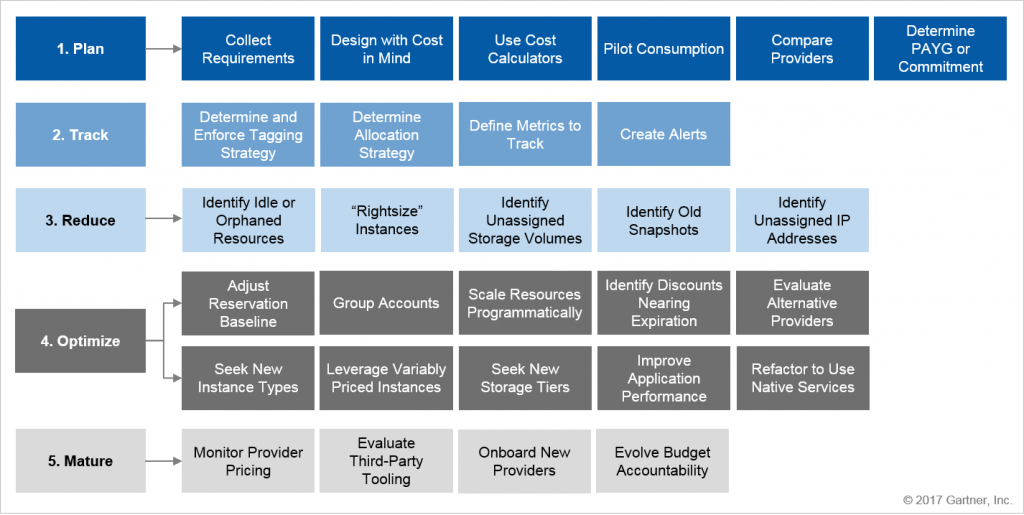

The cloud provider lock-in

One of the reasons behind Amazon’s success is the large portfolio of services they rolled out. They’re all services that can be put together by end users to build applications, letting developers focus just on their core business logic, without worrying too much about queuing, notifying, load balancing, scaling or monitoring. However, whenever you use one of the tools like ELB, Route53, CloudWatch or DynamoDB you’re locking yourself into Amazon. The more you use multi-tenant proprietary services that exist only on a specific provider, you won’t be able to easily migrate your application away.

You may claim to be “happy” to be locked in a vendor who’s actually solving your problems so well, but there are a lot of good reasons (“Why Cloud Lock-in is a Bad Idea“) to avoid vendor lock-in as a principle. Many times, this is one of the first requirements of those enterprises that everyone is trying to attract into the cloud.

Deploying the complete application toolkit

Imagine there could be a way to replicate those services onto another cloud provider by building them up from ground up on top of some virtual servers. Imagine this could be done by a management layer, on demand, on your cloud infrastructure of choice. Imagine you could consume and control those services using always the same API. That would enable your application to be deployed in a consistent manner across multiple clouds, exclusively relying on the possibility to spin up some virtual servers, which you can find in every cloud infrastructure provider.

This is what Tapp is about. And the advantages of doing that are not trivial, these include:

1. Independency, consistency and compatibility

This is the obvious one. For instance, a user can click a button to deploy an application on Rackspace and another button to deploy a DNS manager and a load balancer. These two would provide an API that is directly integrated into the control panel and therefore consumable as-a-service. Now, the exact same thing can be also done on Amazon, Azure, Joyent or any other supported provider, obtaining the exact same result. Cloud providers became suddenly compatible.

2. Extra geographical reach

Let’s say you like Joyent but you want to deploy your application closer to a part of your user base that lives where Joyent doesn’t have a data center. But look, Amazon has one there and, despite you don’t like its pricing, you’re ready to make an exception to gain some latency advantages to serve your user base. If your application is using some of the Joyent proprietary tools, it would be extremely difficult to replicate it on Amazon. Instead, if you could deploy the whole toolkit using just some EC2 instances, then it all becomes possible.

3. Software-as-a-(single)-tenant

If multi-tenancy has been considered as a key point of Cloud Computing, I started to believe that maybe as long as an end user can consume an application as-a-service, who cares if it’s multi-tenant or single-tenant.

If you can deploy a database in a few clicks and have your connector as a result, does it really matter if this database is also hosting other customers or not? Actually, single-tenancy would become the preferred option1 as he would not have to be worried about isolation from other customers, noisy neighbors, et al. Tony Lucas (@tonylucas) wrote about this before on the Flexiant blog and I think he’s spot on, there is a “third” way and that’s what I think it’s going mainstream.

The Tapp’s way

The Tapp technology platform was built to provide all of that. A large set of application-centric tools, features and functions2 that can be deployed across multiple clouds and consumed as-a-service.

Of course it’s not just about tools. It’s also about the application core, whatever it is. The Tapp technology solves also that consistency problem by pushing the application deployment and configuration into some Chef recipes, as opposed to cloud provider-specific OS images or templates3. Every time you run those recipes you get the same result, in any cloud provider. In fact, to deploy your application you’ll just need the availability of vanilla OS images, like Ubuntu 14.04 or Windows 2012 R2 that, honestly, are offered by any cloud provider.

All those end users who want to deploy applications without feeling locked in a specific providers, today had only one way of doing it: DIY (“do-it-yourself”). They would have to maintain and operate OS images, load balancers, DNS servers, monitors, auto-scalers, etc. That’s a burden that, most of the time, they’re not ready to take. They don’t want to spend time deploying all those services that end up being all the same, all the time. Tapp takes away that burden from them. It deploys applications and service toolkits in an automated fashion and provides users just with the API to control them. And this API is consistent, independently from the chosen cloud provider. This is the key value that, I believe, will prevent developers from going straight to the source.

1. Multi-tenancy would be the preferred option for the Service Provider because this would translate into economies of scale. However, economies of scale often obtain cost optimisation and end user price reduction and, therefore, it can be considered an indirect advantage for end customers as well.↩

2. Tapp features include: application blueprinting with Chef, geo-DNS management and load balancing, networking load balancing, auto-scaling based on application performance, application monitoring, object storage and FDN (file delivery network).↩

3. It worths mentioning that pushing the deployment of application into configuration management tools like Chef or Puppet significantly affects the deployment time. That’s why it’s strongly advised to find the optimal balance between what is built-in the OS image and what is left to the configuration management tool.↩